Homer Rhode Jr.

by Ed Mitchell

“The best fly I know for bonefish is the Rhode Shrimp fly which is made of three hackles wound around the shank of a No. 1/0 hook with three hackles going out on each side of the shank pointing backward from the bend, a sort of forked tail. This fly has a lot of action in the water and I like it best in natural (or dyed tan) Plymouth rock hackles. Homer Rhode, Miami Beach Rod and Reel Club, Hibiscus Island, Miami Beach, Florida designed the fly.”—Lee Wulff, in a 1949 letter to author J. Edson Leonard

One of the most intriguing figures in the early days of saltwater fly fishing was a 6-foot-5-inch giant who wandered the wilds of the Everglades—often at night and usually alone. Introverted by nature, he lived a life deeply immersed in the natural world. He loved the creatures of the Glades and knew where they lived, how they conducted their lives and even knew their Latin names. He could catch the fattest snook with a fly rod or the biggest rattlesnake with his hands. The backcountry was his home.

Using a houseboat as a base camp, he spent countless hours in the Ten Thousand Islands, navigating the endless maze of mangroves and shell mounds. Had you encountered him back there, it’s unlikely you could have engaged him in lengthy conversation. He was to-the-point and self-contained. Still, even in the briefest exchange, you might have sensed he was someone special. And if so, your instincts would have been dead-on. Because the person before you was one of those rare people, totally in touch with the planet, a man that had devoted himself to the sun, the moon, and the rain.

Homer S. Rhode Jr. was born on December 10, 1906, in Reading, Pennsylvania, where his father was a local physician. As a young boy, Homer had many interests. During his school days, he was a member of the Gun Club and the Camera Club, and he would be a firearms enthusiast and a photographer for the rest of his life. He was also a versatile athlete. Homer played on the football team and the school’s championship baseball team. Later in life, he would even try out as a pitcher for the New York Yankees. In addition to team sports, he was a purveyor of the sweet science, and good enough to win a Golden Gloves tournament. Yet his favorite pastime was the one he practiced with his father and brothers. Near their Berks County home, there were numerous fine trout streams such as Little Lehigh Creek, Maiden Creek, and Manatawny Creek. It was something Homer, his father, and brothers took full advantage of—for in the Rhode’s household fly fishing was a family affair.

Just after 1925, the family moved to Coral Gables, Florida. It must have been a disappointment for Homer to leave behind the trout streams of his youth. Now outside his window were Biscayne Bay and the Everglades. Somehow, Rhode correctly recognized these waters for what they offered—a brave new world of fly fishing—and he immediately began tying saltwater flies. While there is no record of what his earliest flies looked like, they must have been effective. By 1930, he had landed a bonefish and a permit on a fly, making him one of the first fly anglers in the world to take either species.

Homer married in 1940. He and his wife, Verta, got a place in Coral Gables and quickly had a son, Homer III, and a daughter, Veva. At this point, Homer had lived in Florida for over a decade, time enough to gain an understanding of fly fishing in salt water. In those same years, he had also acquired an encyclopedic knowledge of southern Florida’s wildlife. Whether it lived in Biscayne Bay or the Everglades, he wanted to learn about it. And his fascination with the natural world was reflected in his home. In the yard, he kept raccoons, possums, and armadillos; in the garage, there were terrariums loaded with live snakes; and in the house, snake skins covered the walls.

As the 1940s ebbed, Rhode’s involvement in fly fishing increased. He taught a course in fly fishing at the University of Miami and had become a member of the famed Miami Beach Rod and Reel Club. The fledgling Wapsi Fly Company began marketing some of his patterns. But most important, from his vise had emerged two flies that would significantly influence saltwater fly design: the Homer Rhode Jr. Tarpon Streamer and the Homer Rhode Jr. Tarpon Bucktail. Both flies appeared in Joseph Bates Jr.’s 1950 book, Streamer Fly Fishing in Fresh and Salt Water.

The Homer Rhode Jr. Tarpon Streamer is a simple fly, constructed with splayed hackle wings tied off the bend of the hook and hackle palmered around the hook shank. Rhode described his design rationale in this way:

“You will note that all of my neck hackle and saddle hackle flies are tied with very heavy collars. The divided (splayed) wing flies have the wings tied as far back on the shank of the hook as possible, and the collar is started at that point. This helps to keep the wing from wrapping around the shank of the hook and thus keeps the fly from turning or spinning, at the same time assuring a natural action. In more than twenty years of experimenting with salt water flies, I have found that these features cause fewer refusals, less mouthing of the tail and that I hook more and lose fewer fish. My flies are longer and larger than usual. The heavy collar is due to the fact that I fish very slowly, usually in very shallow water. The divided wing opens and closes like a pair of scissors, making the fly seem to breathe. The heavy collar vibrates when fished slowly, seeming to give the fly added life.”

Even a casual look reveals this fly to be the progenitor of a considerable number of conventional tarpon flies, ones still in wide use today. It is also the source of Chico Fernandez’s Seaducer.

The Homer Rhode Jr. Tarpon Bucktail is an uncomplicated fly as well. Made mostly of bucktail, it has a short tail off the bend of the hook and, tied in at the hook eye, a wing that slants back over the thread body. Joe Brooks acknowledged that he took this basic fly design, fashioned it in several colors and popularized it as his well-known Blonde Series.

Curious and ready to experiment, Rhodes continued to push at the boundaries of our sport. Beyond chucking feathers at bonefish, permit, tarpon, spotted seatrout, and snook, Rhode cast to mullet and snappers with trout-size fly gear. For snapper, he used scaled-down flies made of white or yellow polar bear hair and then attached one or two spinner blades up front. Working around mangroves and even over shallow reefs and wrecks, he refined his technique until he could take snapper successfully. His approach to mullet took a more radical venture into what one might call ultra-light saltwater fly fishing. Realizing that mullet were algae-eaters, Rhode understood his flies would have to be tiny. So he tied them on hooks down to size 16 in white, light green, yellow, and black and then attached them to leaders tapered down to 4X. His largest mullet was 5 ¾ pounds; it burned 150 yards into the backing while leaping like a demon. (It makes you wonder how many species we are overlooking even today.)

Although he was active on many fronts, a brand-new challenge caught his eye. The recently formed Florida Game and Fresh Water Fish Commission had decided to organize its first band of conservation officers. Wasting no time, he enrolled. And when the first graduating officers lined up for a class photograph, Homer Rhode Jr. was one of them.

Enforcing game laws in the Everglades was desperately needed, yet wandering in the backcountry without any real hope of backup was clearly a dangerous business. Back then, southern Florida was as lawless and untamed as any place on earth. Here, where the temperate zone meets the tropics, you had gators, crocs, snakes, sharks, and clouds of mosquitoes thick enough to choke a horse. Worse yet, hiding in the buttonwood hammocks were varmints of the two-legged kind. The Glades were infested with criminals. At any moment, you could be face-to-face with poachers, smugglers, moonshiners, or even murderers—none of whom wanted a lawman around. So it’s no real surprise that, while on duty, Rhode would find himself in a gun battle. A crack shot since a kid, he came out on top, yet in the process was forced to kill a man.

After that unfortunate incident, Rhode hung up his badge and spent the next three years fly fishing commercially for snook; it was legal at the time. Working the waters around Everglades City, Marco, and the Tamiami Trail, Rhode fished day and night, filling up a big wooden ice chest built into his car. He made two daily trips to the Miami market, selling his catch in at six cents a pound. That might not sound like much, but on a good day, he’d bring in half a ton. To do that with a fly rod speaks volumes about Homer’s skill, but his intimate knowledge of the natural world played a role, too. While driving the Trail at night, he would keep an eye peeled in his headlights for leopard frogs plastered to the pavement. Rhode realized that wherever the frogs showed up in number, the snook would be waiting in the water alongside the road. Stopping the car, he would jump out with his fly rod, all the while being careful: Rattlesnakes and cottonmouths were fond of the frogs, too.

Eventually, he took a job with Miami-Dade County. In an unfortunate accident, he was exposed to a powerful rodenticide. It damaged his nervous system, weakening his arms and legs and forcing him to retire with a disability. On the upside, it allowed him more time on his houseboat near Chokoloskee. Roughly 30 feet long, it was a rustic affair, with the only creature comforts being piles of books. Still, Homer loved this simple retreat, not only for the solace it offered but also for the freedom to spend unlimited hours exploring his favorite waters.

Homer Rhode Jr. passed away on July 7, 1976. The loop knot that bears his name is widely known, of course, yet the true extent of his contributions to our sport have remained largely hidden. To a degree, we can attribute that to Homer’s humble personality. Reluctant to be in the limelight, he deliberately kept himself out of it. Regardless, this much is clear: Homer Rhode Jr. was a pivotal player in the dawning days of our sport, and he richly deserves to be ranked as a pioneer and remembered as a man of many skills. He was a fly-rodder, naturalist, game warden, guide, amateur herpetologist, commercial fisherman—the list goes on and on. And because of this, it is clear that behind his quiet exterior there lived an exceptional mind. As the old proverb goes, “Still waters run deep.”

The author would like to thank several members of the Miami Rod and Reel Club: Captain Dan Kipnis, Suzan Baker, Jack Holeman, Steve Roadruck, and Cromwell A. Anderson. He is also indebted to Gail Morchower of the International Game Fish Association, the late Lefty Kreh, and sporting book dealer Dave Foley. Above all, he would like to express sincere thanks to Homer Rhode Jr.’s son, Homer Rhode III.

Bio: Ed Mitchell is a writer, photographer, and lecturer with extensive fly fishing experience in fresh and salt water. He has written for all of the major fly fishing magazines and is the author of four books on the subject. Ed lives in Punta Gorda, Florida. His website is www.edmitchelloutdoors.com.

“One night Homer and I left his houseboat in a tin boat to do some fishing. Guided only by stars and the ink-black silhouette of the shoreline, Homer steered his boat through the labyrinth of the Ten Thousand Islands. Eventually we arrived at a spot loaded with snook. The following morning, back at the houseboat, I suggested a return trip. Homer paused and in a quiet voice said we couldn’t. He did not know how to get there in the light of day.”—Lefty Kreh, in interview with Ed Mitchell

HOMER RHODE JR. FLY RECIPES

Homer Rhode Jr. Streamer

Hook: Size 1 or 1/0 for bonefish, to 3/0 for tarpon.

Wing: Six saddle hackles tied divided (splayed) at the bend of the hook.

Collar: Three hackles wound from the bend of the hook toward the eye.

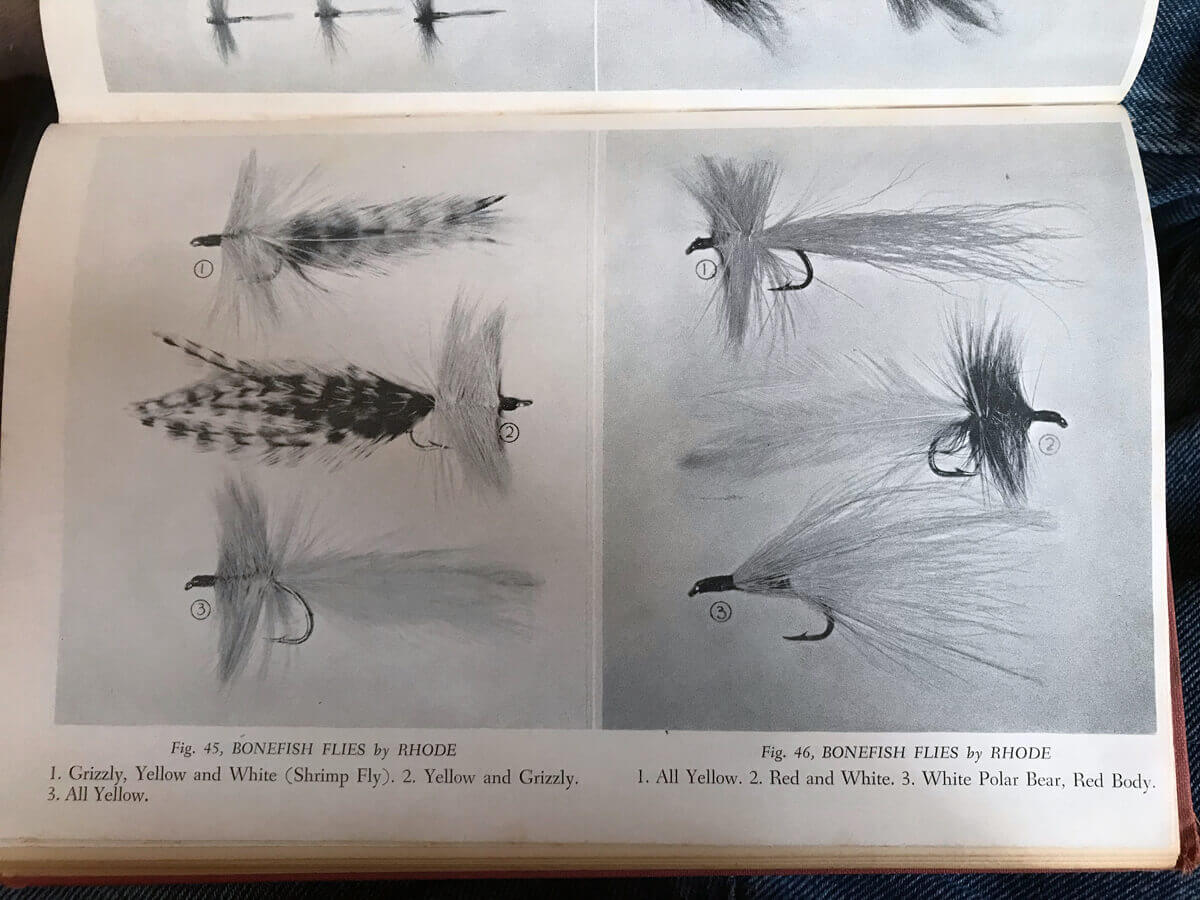

Notes: Also referred to in the literature as the Homer Rhode Shrimp Fly, Rhode dressed this streamer in a number of color combinations, including a wing of yellow, grizzly, and white hackles collared with yellow and white hackles; a wing of grizzly hackles and a collar of yellow hackles; yellow wing and collar; wing of white hackles and a collar of red hackles. Lee Wulff’s favorite version for bonefish was grizzly hackle in natural (pictured) or dyed tan for both wing and collar.

Homer Rhode Jr. Bucktail

Thread: Red.

Hook: Size 1 or 1/0 for bonefish, to 3/0 for tarpon.

Tail: White bucktail secured along the shank with thread.

Overwing: White bucktail, as long as the tail, tied in just behind the hook eye.

Homer Rhode Jr. Bucktail (Version 2)

Hook: Size 1 or 1/0 for bonefish, to 3/0 for tarpon.

Wing: Yellow bucktail tied in at the bend.

Collar: Three yellow hackles wound from the bend of the hook toward the eye.

Notes: Mr. Leonard’s book makes it clear that the tail and wings in the above two patterns were originally tied using polar bear (now endangered).

SUBSCRIBE TO TAIL FLY FISHING MAGAZINE

SUBSCRIBE TO TAIL FLY FISHING MAGAZINE